About Us

OUR STORYThis is how we got started.. scroll down to read the whole story.

Origins

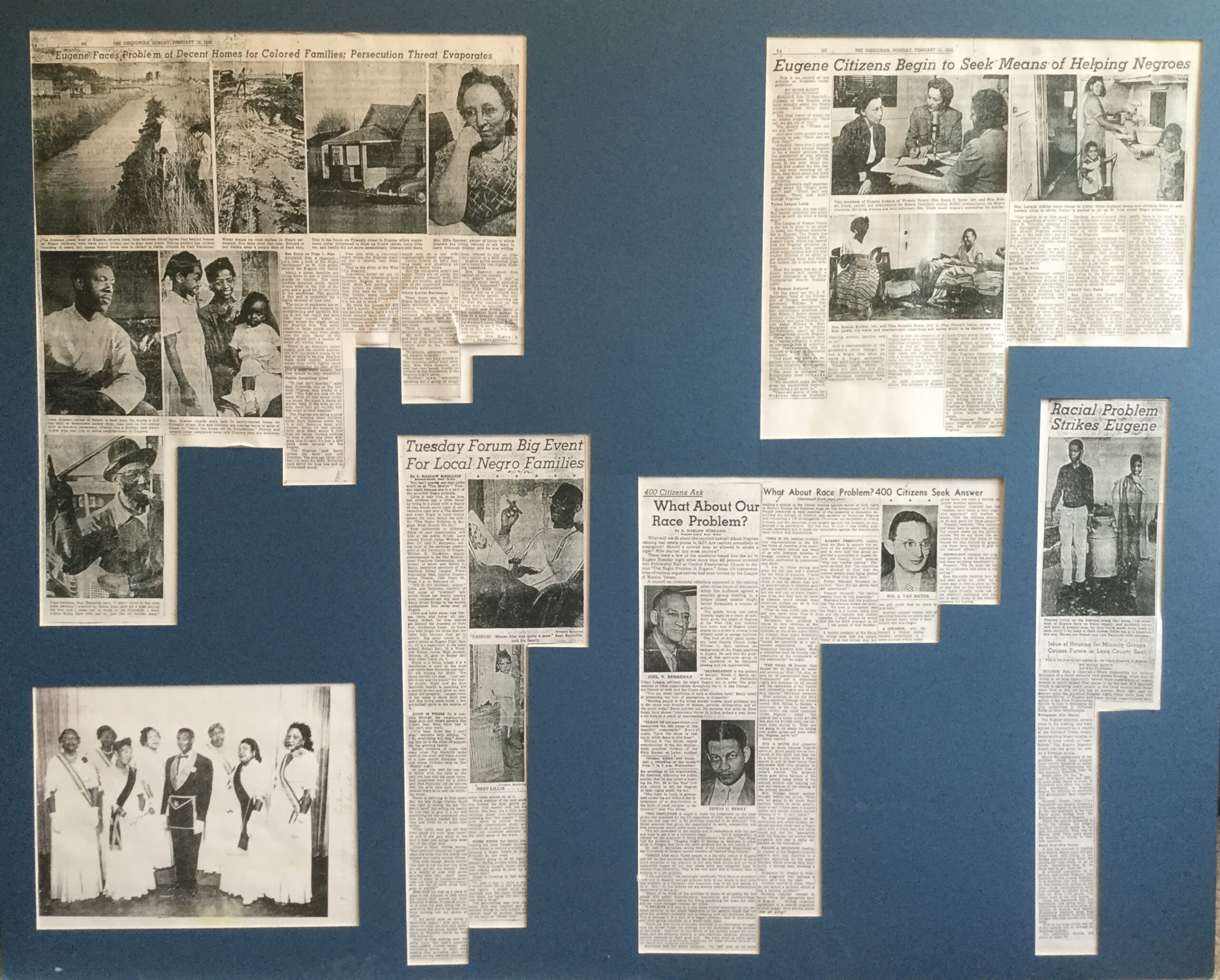

In 1997, our youngest son’s third grade class, was the only class in his school, to both teach aboout the upcoming Martin Luther King Holiday, and observe Black History Month. Since Black History Month in schools typically consists of Slavery, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, Cheri didn’t want to do that. Our own home training for our kids, went beyond that. Cheri decided to research what was happening here in Eugene. Oregon is a Southern State in the Northwest and therefore a Civil Rights Movement in Eugene, was necessary. Since 1993, We’d had personal possession of three Black History Panels. These panels were assembled by two African-American sisters, Bridget Fahnbulleh, and Star Jackson.

The sisters assembled three panels from clippings at the YWCA and gave them to Mark, for future use. These panels were displayed as part of our contribution to the Northwest Black Pioneers Exhibit in Valley River Center in 1997. The would also be used in “Tent City Re-enactments” in Alton Baker Park, by LCC’s Black Student Union.

The panels told an incomplete, but compelling visual story, that generated even more questions.

Who were the kids carrying water? Why would they have to in the 1950’s?

Who was the woman playing Aunt Jemima at the Logger’s Breakfast in Springfield?

What happened to the Ferry Street Chapel?

Why was there a problem with the “Negro Settlement”?

Bridget & Star’s Panels

Bridget and Star in addition to founding The Martin Luther King Jr. Theater Company had attended the IAAM, (Institute for African-American Mobilization), a four-day culturally specific prevention training, that Mark was a curriculum writer and trainer for. Part of the IAAM design called for a discussion of local Black history. The team knew generally about Oregon’s Exclusion Laws: In effect outlawing slavery by a complete ban on Black people. Unlike other cities the IAAM had been hosted in, there wasn’t a “hood”, a “barrio”, a “Chinatown”, a “rez” or an ethnic neighborhood. The IAAM team tried to get that history from the UO, The City of Eugene…etc. To no avail.

In 1997 Cheri decided to do a deep dive into the University of Oregon’s microfilm archive in the Knight Library. Searching through the earliest newspaper records in the mid-19th Century, she did a painstaking day by day search from then to Spring 1997.

As part of that original research, Cheri found the “classic”. picture of Wiley Griffon, so we have her to thank for bringing that to public awareness.

About Us

In 1997, our youngest son’s class, was the only class in his school to both teach on the upcoming King Holiday, and to do a unit on Black History Month. Since that usually consists of Slavery, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, and the Civil Rights Movement in the South, Cheri decided to research what was happening here in Eugene Oregon during 50’s and 60’s Civil Rights / Black Power time. We had possession of three Black History Panels, as a start. Cheri decided to do more. Professional Black historians, had told us, “there was no history worth mentioning in Eugene.” We wondered why they hadn’t spoken to actual Black residents of Eugene, who had courageous and traumatic stories to tell. Why were they not being told, even by Black historians?

We felt there were very strange gaps in the available literature, which at the time for us consisted of Peculiar Paradise, The Story of Eugene, and the City of Eugene’s Historical Context Statement.

The context statement read: “The struggle of non-white groups in early Eugene, though often understated, is an important part of the community’s history. Cultural groups that resided in or near Eugene City during this initial period of growth and development included Native Americans, African Americans, Chinese and Japanese.There is little information regarding the occupations or residency of these groups in Eugene specifically, but it seems that tolerance for the non-white population was low.” – City of Eugene Historical Context Statement

So, they say that there is a struggle, but make no moves towards correcting, improving, or aiding that struggle. Why? Was there really nothing, or a gentlemen’s agreement to silence any questioning. Ralph Hayes, of the Northwest Black Pioneers in Seattle, co-sponsor of the exhibit in Valley River Center next to the Bon Marche, looked at the panels, lauded and warned us: It can be a dangerous thing to unearth hidden truths. Some people would rather they remain hidden, others may take credit for your work, by not mentioning, or ignoring you. Keep fighting the Good Fight.

Cheri started researching 5 different newspapers, day by day, from the 1850’s to 1997. What she found began to explain some of the historical trauma we were sensing when talking to elders in the African-American community, and their white allies, who had grown up here, in the civil rights movement. There was a civil rights movement here, which means there was a need for civil rights struggle, with the usual sheroes, heroes, villains, bystanders, neutrals, and allies.

Cheri’s research of the newspapers indicated there were people of color here in Eugene from its inception. But, with respect to Native-Americans, (Reported in The Story of Eugene, as “dusky Kalapuya maidens”), and African-Americans, there was particular hostility, expressed in the exclusion laws, redlining, sundown laws, real estate land covenants etc. There was a Chinese presence, a Japanese and Hawaiian presence, and an Arab presence, and a Jewish presence. Nonetheless people thrived, after a fashion. In the example of Wiley Griffon, Cheri found him, by going to the bus station and talking the union organizer and historian, Paul Headley. Initially it was to answer the question of whether the buses were segregated, as in the example of Rosa Parks. Paul gave us the picture of Wiley Griffon, and the union contributed the initial money to replace Wiley’s headstone in the Eugene Masonic Cemetery, which apparently had been lost, around 1959.

Our First Projects

In 1998, Among our first initiatives, which included honoring Wiley Griffon, who wasn’t the first African-American in Eugene. There were 250 African-Americans in the Oregon Territory around the Exclusion Laws 1844 – 1859. Several were asked their opinion of the Emancipation Proclamation Jan 1, 1863. But they weren’t identified, as they could be arrested and deported, after up to 3 years labor, or posting a thousand dollar bond. Wiley was the first mentioned in the historical record. Our first project after receiving his picture, was to replace Wiley’s headstone in the Masonic. The headstone originally estimated at $1900, of which we had raised $1200, suddenly had to become a historical monument topping out at over $5000, finally installed in 2013. Commemorative plaques at LTD’s then new downtown bus station, and his old homesite which was now EWEB’s parking lot. That proposal went out in 1998. LTD was the first to create a plaque for Wiley. Successive CEO’s of EWEB either thought “$500 for a plaque was too expensive”, or simply didn’t reply to our inquiries. Finally around 2016, a commemorative display was placed.

From time to time what we call “United Nations” approaches to racism, draw people together one Red, one Yellow, one Brown, one Black. A community forum on racism in Eugene / Lane County, was going to be held in the old City Council Chambers…without any Native American representation, because the white organizers “didn’t know any Native Americans.” We knew several including Esther Stutzman, whom we called, and she was invited to speak on the panel. Her chance remark at that event: “There were no signs acknowledging her people were ever here” led to the creation of the Kalapuya Talking Stones, and eventually a new freeway bridge over the river, and renaming Eastern Alton Baker Park as Whilamut Natural Area, and a section of the downtown riverfront park.

In the year 2000, We sought and received seed money from the City of Eugene, to produce a curriculum for the Eugene School District. Acceptance and implementation of that curriculum, became stalled. Oregon history as taught, still remained limited to a video game, Oregon Trail.

Mark took a portion of the African-American I Too Am Eugene, material and began using it in LCC’s Rites of Passage program, occasionally publishing pieces in the local newspapers, sometimes radio, and in LCC’s recreated Ethnic Studies Program in 1998, where he continues to the present day. In 2017, he taught a African-American Experience in Eugene for the University of Oregon. Drawing from, and expanding upon Cheri’s original research, which detailed a history of African-American resilience, academic and professional excellence, and social activism.

But also where there are efforts to progress, there is active resistance to progress in the form of the usual suspects: an active and continuously operating Ku Klux Klan. The Klan initially centered in the University, City and County Government, Law Enforcement, The Chamber of Commerce, various businesses including the news media, notably the Register Guard, and others, with the dominant mythology that Eugene Klan #3 had died out in 1925. A lie which continued to be repeated, but is not the experience of the Black Community, White Allies, opinion of the Intelligence community which studies the behavior of domestic terrorist groups. If the Klan died in 1925, why did the Oregonian say they claimed 16000 members statewide and was going use Eugene as their state headquarters again in 1937. Who is burning crosses in 1952, and into the 70’s? Who is organizing among labor forces in the major employers into the 21st Century? Along the way we’ve collected several related publications which added to the visibility of people of color in the historical record. We’ve also participated in many historical exhibits and presentations, including DiversiTV, Chamber of Commerce, Racing to Change, Strides for Social Justice.

We are activist historians. We believe that the healing of old wounds requires the telling of difficult truths. That primarily means as community based people, with relationships to communities of color, we will go places, to find and reveal things that “professional historians”, connected to Universities won’t often do. Cheri’s research uncovered the presence of the Ku Klux Klan, organized out of the University of Oregon, and essentially infiltrating most of the major institutions of the community. Though, given the founding of the state, and its racist legal infrastructure, racists weren’t infiltrating, so much as finding ready acceptance, in the business, professional, political, law enforcement, and legal communities. Which of course means that there were people opposed as well. To date, as of 2021, no Eugene news outlet, or institution, other than LCC has published the century old KKK membership list. Even though the list has been corroborated by law enforcement, degrees have been awarded, it has been confirmed and published in the Salem paper, a century ago. The Klan and its adherents continued to organize well past the death of its first Exalted Cyclops Frederick Dunn, in 1937. In that year, the Oregon Klan, boasted more than 16,000 members statewide, intended to organize in politics and law enforcement, and make Eugene its state headquarters, again. The African-American community started growing then, and reported weekly cross burnings, which were not reported in the press. One wonders how one can authoritatively state the Klan died in 1925, when the experiences of the Black community, law enforcement, and intelligence communities indicate, Klans don’t die, they go underground. But, I Too Am Eugene, like its poetic namesake, the Langston Hughes poem I, Too Sing America, wishes to tell a story of progress as well. But we cannot shy away from difficult truths.

Our Praxis: Since 1997

Power is a History that is remembered and known. If you have a visible known history, you have political and cultural agency in the present and future. We’ve been co-creating and participating in the creation of monuments, memorials, street names, curriculum, apps, specials on educational television, video presentations, classes, and websites.

I Too, Am Eugene participated in making people of colors’ history visible: Talking Stones, Wiley Griffon, MLK Blvd, Sam Reynolds Street, then supported Japanese-American Memorial at the Hult Center, Mims House & “Across The Bridge” memorial. We believe that cross-cultural alliances are part of the traditional strength of civilizations on this continent.

Our Mission, Vision, and Logo

I Too, Am Eugene: A Multicultural History Project is committed to revealing hidden history, to promote multiracial understanding in a changing world.

Our logo is an African Crossroads, combined with one version of a Native American Medicine Wheel. Mark identifies as a Yoruba-Choctaw maroon. One version of the Medicine Wheel among the Lakota, and the Tsalagi / Cherokee, depicts the Pre-Contact origins of Four Nations of Humanity. To the East, the Yellow Race, to the South the Black Race, to the West, the Red Race, to the North, the White Race. Each race was given a piece of the Truth, by Creator, then scattered to the Four Directions. In some of the stories, the whole truth cannot be known till they all come together and share what they know. This could be called Quadriunital Logic. The African Crossroads depicts four smaller circles which represent “Emic” culture, that which is generated inside a culture and is only visible to cultural insiders. The larger circle is visible and often misinterpreted to “Etic” cultural outsiders.

Get Involved

Help expand the work. Donation buttons and website additions coming soon. Wiley’s memorial has become a shrine of sorts, with people leaving coins, flowers, crystals. There are other graves, where he’s buried, who knows what stories lie buried in our community.